"We did have one woman in leadership," the firm owner said during a lunch and learn that I was attending. "She decided she wanted to spend more time with her family. At some point, you'll have to choose," he continued.

The person speaking was one of more than a dozen firm leaders in attendance (ALL identifying as men), several of whom I knew were married with children.

That fact seemed to escape the speaker’s notice, but it certainly didn't evade mine.

At that point, I stealthily snuck out of the back of the room so I could lock myself in the bathroom stall and cry. I vaguely recall my manager asking me later that afternoon if I was OK, as I was coming to grips with the fact that my work reality didn't align with my expectations.

I told him I was "fine" (when I was far from it) and attempted to bury those emotions instead of facing what had just happened.

This would be far from the last time I struggled with my own high emotions at work.

And for a long time, I directed that energy towards the wrong places.

I'd get angry and vent to my husband and friends after work.

I'd choke down tears (again) and internalize what was said to mean there was something wrong with me.

I'd freeze and then later think of all the questions I should have asked to get clarification. I found myself fixating on what I should have/would have/could have done instead of freezing up in those moments.

If you are a high achiever and take pride in your work, you have experienced situations like these. You’ve experienced times when you showed up as less than the professional you are as you struggled to absorb what just happened. Perhaps you said something that stoked a conflict instead of resolved it. You may even have left a job over a conflict situation, such as differences between yourself and your manager that couldn’t be resolved.

You are far from alone in struggles with conflict.

This study found 85% of workers said they deal with some conflict at work, with 29% saying conflict occurs “always” or “frequently.” This same study found that U.S. employees spend 2.8 hours on average per week dealing with conflict, which means conflict costs employers $359 billion in paid hours (based on average hourly earnings of $17.95).

Staying professional during conflict is a learned leadership skill

As I wrote in She Engineers, successful STEM professionals share a number of “most valuable traits”, what I refer to as MVT’s. One of them is staying calm in chaotic and stressful situations.

In my book, I shared a number of statistics focused on how the inability to manage emotions can be hugely detrimental to your career path, especially for women and non-binary individuals. This particular MVT can be the difference between a career on your terms and a career of struggle.

It is also statistically likely that those who don’t fit the stereotypical mold are more likely to experience more conflict earlier in their careers than others.

For example, according to a 2017 Pew Research Study, 79% STEM women and 52% STEM men report that they constantly feel the need to prove themselves at work. This can lead to conflict purely because many of us see our work as an essential part of our identity and take feedback to heart, resulting in defensiveness and high emotions when things are not going well.

For women, conflict often initially appears in the form of microaggressions. For example, a case of mistaken identity as the secretary or a comment on one’s curly hair or attire can lead to a greater conflict down the line, where those comments add up to a general feeling of being unappreciated, taken for granted, and disrespected.

Statistically, according to the 2019 LeanIn.Org Women in Workforce Report:

52% of women report that their expertise has been questioned

64% report being interrupted or talked over at work

27% report being mistaken for someone at a much lower level

45% report having others take credit for your ideas

Additionally, for those facing harassment and discrimination, you are often forced into conflict to resolve the situation.

50% of women in STEM overall and 74% of women in computer-related jobs say they have experienced discrimination in the workplace.

Regardless of their gender, individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic, or Asian are reported to have experienced alarming rates of workplace discrimination at 62%, 42%, and 44% respectively.

Yet, simply speaking up about discrimination or harassment at work is often perceived as creating more conflict.

The reality is that to simply function at work, women, non-binary individuals, and those in underrepresented racial and ethnic groups must learn to effectively deal with conflict earlier in their careers than their counterparts.

This isn’t a “nice to do”, rather it’s a survival tactic. Managing those reactions is necessary to counteract the unconscious and conscious bias these groups are statistically much more likely to encounter than their counterparts, at both a higher frequency and far earlier in their career paths, often even within that first internship or job interview.

Mastering your own emotions allows you to show up as the authentic current or emerging workplace leader you are. This essential leadership skill is one that I see consistently among women, non-binary individuals, and ethnically diverse people who rise in the ranks of their organizations quickly.

What happens to your brain during conflict

Our brain processes 11 million pieces of information per second, all stemming from our 5 senses. To process this information quickly, only about 5% of our brain’s activities are conscious.

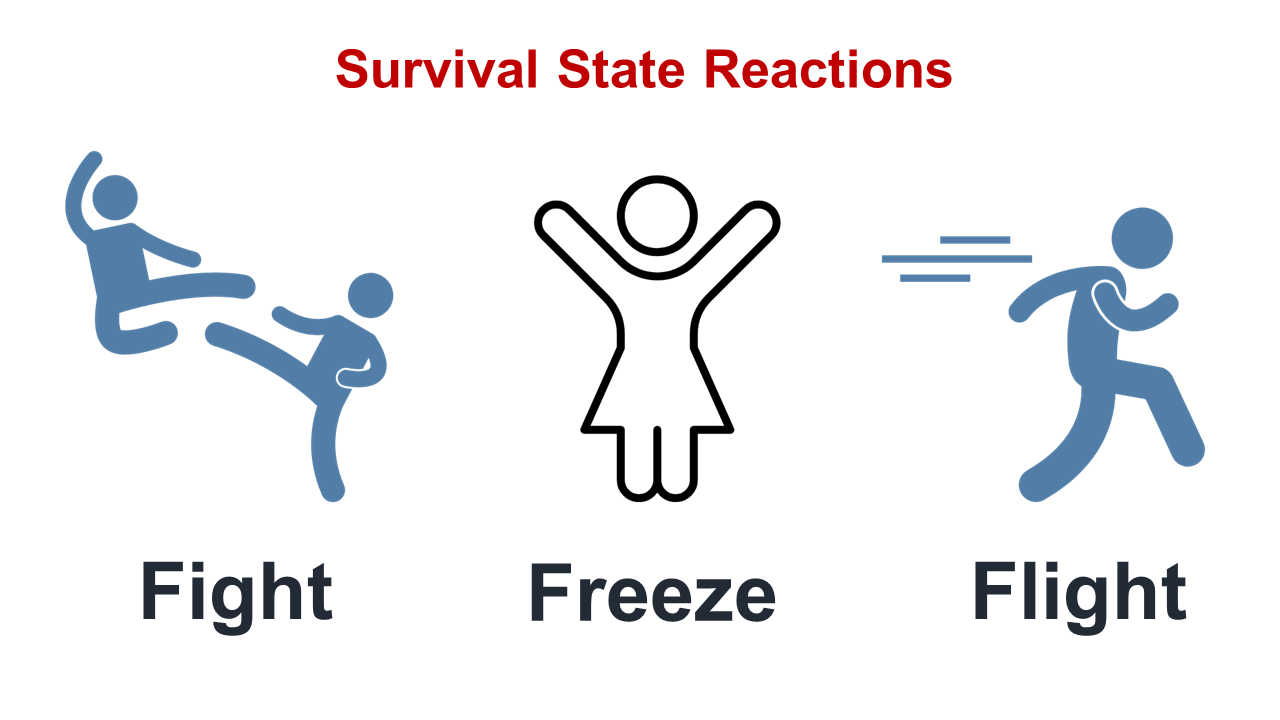

When we are triggered by a person or situation, our bodies undergo a physical reaction from our unconscious brain. This response is often referred to as the flight, fright, or freeze states. These states are conditions of being human. We cannot stop our biological initial reaction to a specific situation.

These states have a direct impact on our physical bodies. For example, it is common to experience shallow breathing and a fast heart rate when your body is in flight, fight, or freeze mode, or what I refer to as “survival” state.

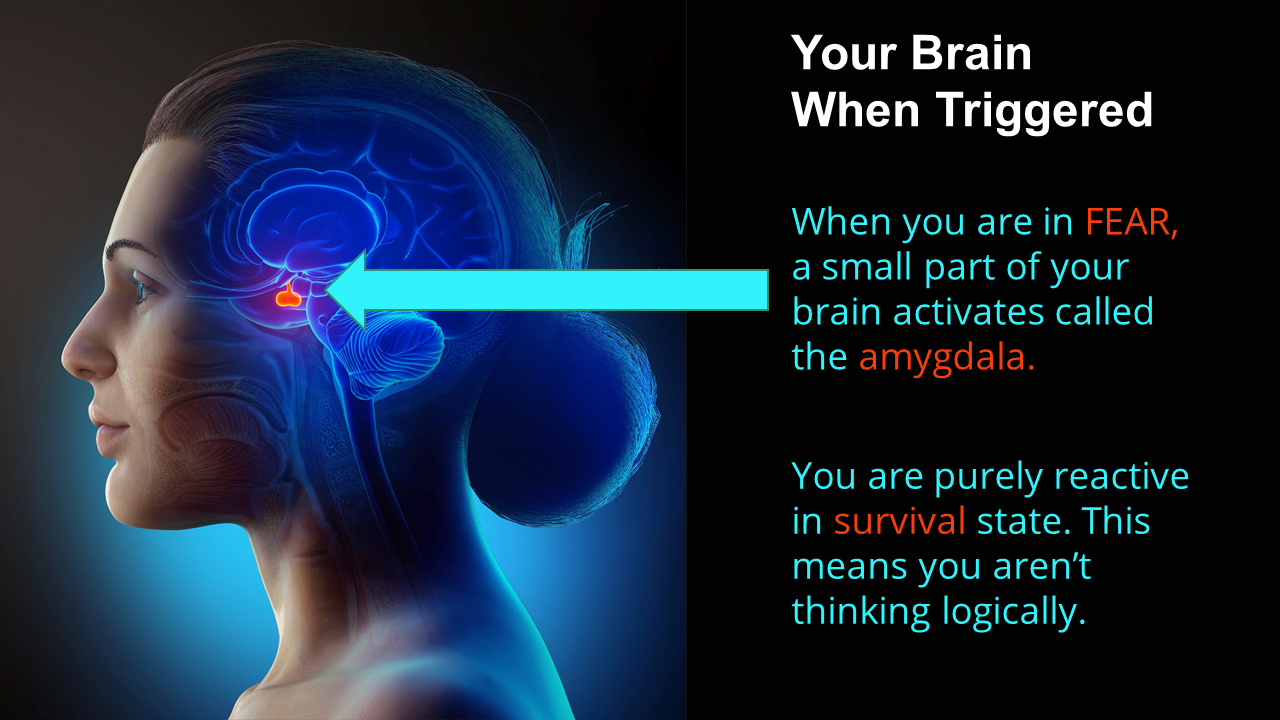

This is an indication that your body is equipping itself to fight or run away in response to a threat. Our bodies have no way to distinguish between a true physical threat on our lives and our trigger response to a coworker’s annoying comment. When triggered in these moments, we are experiencing fear and the activation of a small part of our brain: the amygdala.

Once the amygdala is activated, we are in a pure survival state of being. Our bodies increase blood flow to our extremities and major muscle groups in preparation for a physical response. Work stress and other triggering events can cause this reaction, leaving you physiologically unable to think rationally unless you remove the threat, or use the technique shared later in this blog to reframe it.

The key to understand is that when your brain is in survival state, you aren’t able to access those problem-solving strengths engineers are known for. It’s kind of like a light switch, in that your brain is either in survival state or in a problem-solving state. Your brain can’t be in both states at the same time.

Again, there is no stopping the initial reaction. Everyone experiences high levels of stress, especially when criticized or questioned.

The good news is that you CAN teach your brain to flip the switch and get yourself out of survival mode quickly. With practice, you can learn to flip that switch in just a few seconds for most triggers (longer for more egregious ones) so that you can move forward professionally, regardless of what is thrown your way.

A framework to stay calm, even when triggered (hint: it takes practice!)

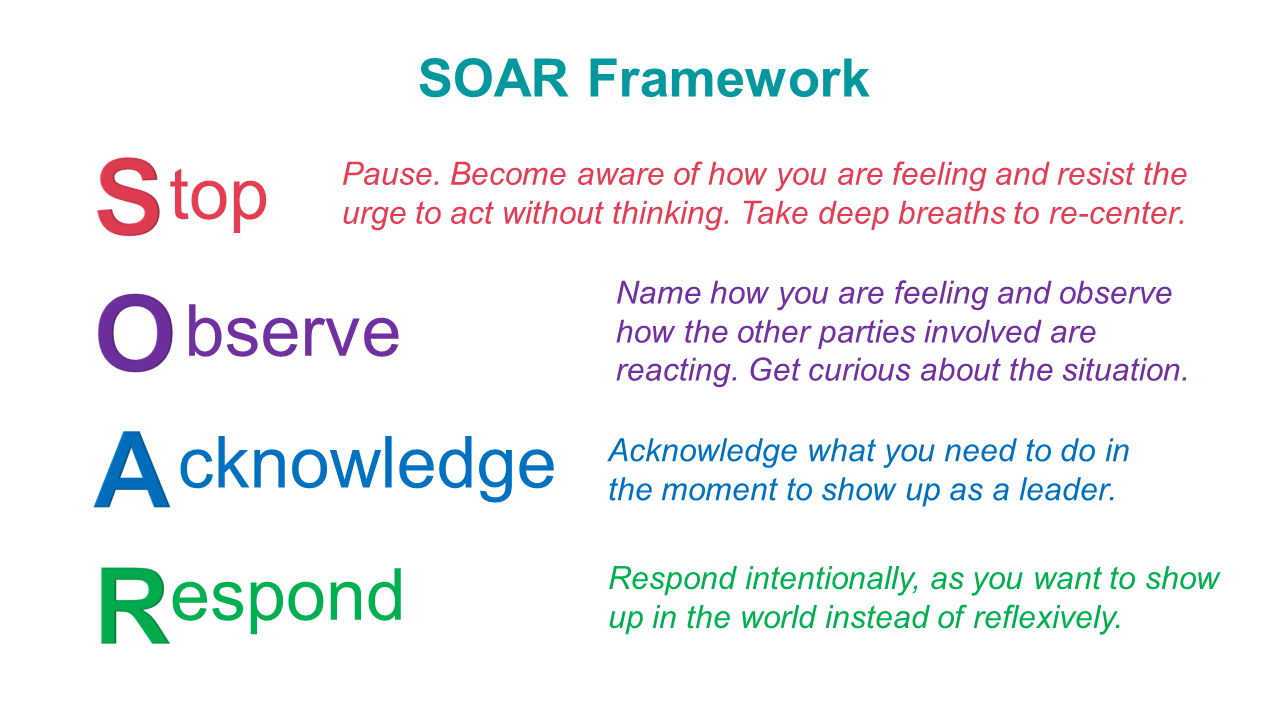

A simple framework you can use to manage your emotions and move forward professionally is “SOAR.”

SOAR stands for:

Stop

Observe

Acknowledge

Respond

S is for Stop. In that moment, you have to STOP before you react.

Stopping is often the most difficult step, and it’s also the most common mistake STEM professionals make when dealing with conflict. Instead of stopping to mindfully consider our response, we start reacting, often in ways that do not serve our reputations. I can’t overemphasize the sheer importance of stopping before doing anything else.

Examples of techniques that you can use to stop include: taking a few deep breaths, getting a sip of water, or buying yourself some time with an “ouch” or “hmm” remark in response to what just happened, followed by your silence. Your goal with stopping is to bring your awareness to the moment so that you have time to decide how you will react.

O is for Observe.

Observe how you are feeling. Name it.

A is for Acknowledge.

Acknowledge what you need to do in the moment in order to be able to show up as the person you want to be in this situation. Do you need to step away from the situation? Do you need to defer the conversation to another time? Can you take a few breaths and be back on track? Can you practice curiosity? Sometimes you need to do a combination of all four.

R is for Respond.

It’s time to respond to others in the way you want to show up in the world.

With practice and moving step-by-step through the “SOAR” method, you will find that you can access and engage your problem-solving abilities with ease.

For some problems – the big and very personal ones – you may find you need to dwell on the “Acknowledge” step a bit longer before you can respond appropriately.

This framework gives you the right to CHOOSE how to react to a situation, so you can show up intentionally and authentically in your career.

For further explanation and a step-by-step application of this framework and an application example from my own career during a meeting where I was called incompetent, please check out the video below.